Magic Mountain

Chapter 2 - Raising a Mountain

Estimated Read Time: 17 min

This is Chapter 2 in a multi-part series of Magic Mountain. For Chapter 1, click here.

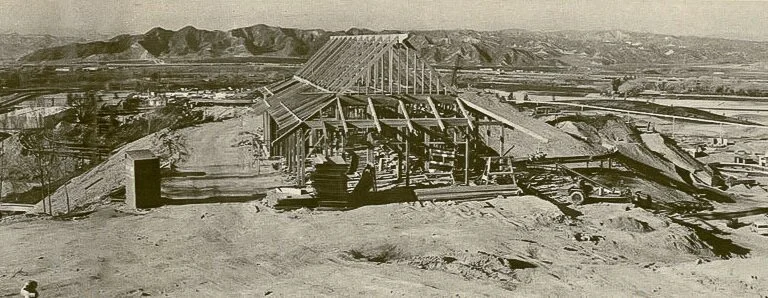

On April 19, 1971, forty days before Sea World’s new rides park was scheduled to open, a reporter from The Signal was granted a tour of the construction site. The reporter was met by a public relations representative and was whisked around the property in a motorized cart. The cart slogged through the park’s still unpaved, muddy pathways. The mud was “thick and oozing—the kind seen in Western movies for the inevitable wrestling match”. The reporter was humored and perplexed. There was six weeks to go, and the new theme park was still very much an active construction site.

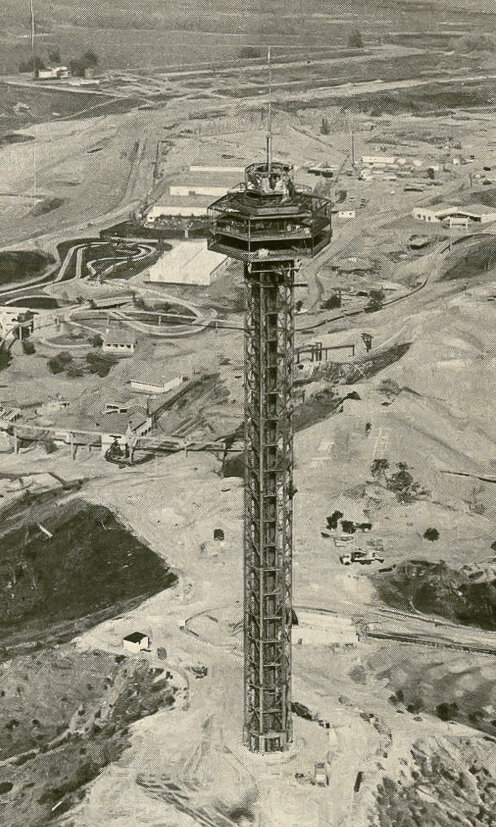

Aerial photo of a nearly-complete Sky Tower amidst a frenzy of construction. March, 1971.

Unpainted, “burnt-red steel” rides stood silent. Ponds and artificial concrete lakes rested dry and unfilled. Trees were bound and boxed, awaiting their turn to be planted. The cart wizzed past dormant rows of log flume vehicles in the parking lot, awaiting their installation at the still rapids-less Log Jammer. In fact, quite a few rides were still under construction. All the meanwhile, the park representative waxed on about the park’s many dance venues, restaurants, and the newly painted buildings.

As the public relations man drove the cart up a small hill (on the way to the next tour stop, a chicken restaurant called “the Painted Pullet”), the mud defeated the tiny vehicle. The cart began to swerve and sputter on the slick ground before getting stuck in a hole. The “PR man and the reporter” stepped into the sludge and began pushing and prying the stuck vehicle, hoping it would break free from the suction-cup terrain. They placed wooden slats in the hole and fought to gain leverage or give traction, but cart wouldn’t move. Finally, the two crunched down and managed to lift the car up and out of the muddy ditch.

Exhausted and dirty, I imagine, the two got back into the cart and the tour continued. As did construction on a theme park rapidly running out of time to finish.

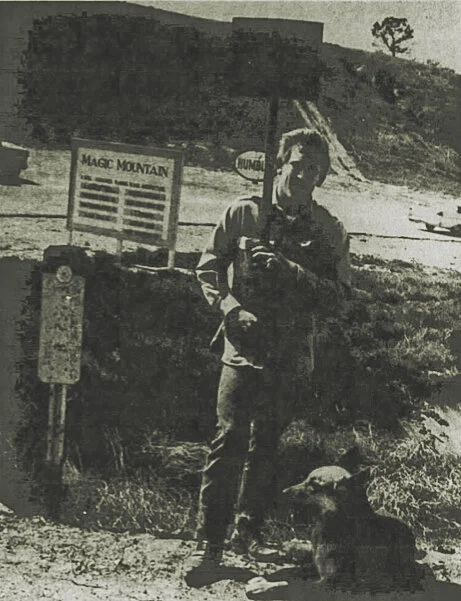

The Valencia Rides Park Gets Rides

By October of 1969, things began to move fast for the upcoming Valencia Rides Park. Locals were now supportive of the project. Government zoning approvals were finally coming through. The earthquake risk assessment survey had been scheduled; building permits would follow soon after. All of the park’s rides had been ordered and a construction plan was developed. And while Sea World had yet to officially land on a name, a logo concept was approved (a mountain, ringed by a rainbow). Throughout November, additional financing was secured (backed primarily by the Newhall Land and Farm Company). And in January, Sea World made it official—the park would be called “Magic Mountain”. Doc Lemmon’s place-holder name would shine through, after all.

And then, nothing. For months, residents looked to the mountain hoping to see the park taking shape, but saw no significant construction. During this time, construction efforts were primarily focused on clearing the land and building support structures, like administration offices and warehouses. But in August of 1970, with 9 months to opening day, locals were treated to their first sign of progress—a sign. At the Saugus exit of the new Interstate 5 freeway, an offramp sign appeared for “Magic Mountain Parkway”. And in September, locals were invited to visit the park’s “Hospitality House”, a preview center for the upcoming theme park. Featuring artist renderings, a carousel horse, a Grand Prix car, and a scale model of the theme park, the Hospitality House operated five days a week to seed excitement for the upcoming park. They could also see that the pace of building construction and ride installation was picking up, particularly with the start of vertical construction on the park’s Sky Tower.

Manufactured by amusement industry-giant Intamin A.G., the Sky Tower is the park’s 384 foot tall hexagonal observation tower, topped with two stacked viewing platforms. The top platform was fully enclosed (it was designed to serve as a sky-high restaurant) while the lower platform provided open-air viewing. The observation decks were to be accessed by two, 50-passenger elevator cabs. The whole attraction cost $800,000 to build.

Concept art for a Hexagonal Tower, showcasing a tower’s advertising-potential.

Legend has it that Magic Mountain’s Sky Tower was originally slated for Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Club, in Chicago. In fact, Intamin produced Hexagonal Tower concept art with the club’s name etched into the vertical truss and the company’s signature bunny icon poised high, atop the tower. Whether or not Magic Mountain actually scooped up the Playboy tower isn’t clear to me. But in August of 1970, the painted-white prefabricated steel components of the Sky Tower, matching the Playboy concept art, began to arrive in the Los Angeles Harbor. Soon after, construction workers began pouring six 80-foot deep forms to serve as the foundation for the Sky Tower, giving the structure enough strength to withstand winds of 120 miles per hour. Once the foundation was set, vertical construction would begin. By December, the tower was 1/3 complete; in January, the observation decks were installed. The interlocking construction was performed by local bridgeman contractors Aggressive Erectors. If the whole attraction didn’t already seem too phallic for a Playboy Club, Aggressive built under the slogan “Satisfaction Guaranteed with our Erections.” While the Sky Tower was Aggressive’s biggest erection, the contractor would also install several flat rides for Magic Mountain, including Billy the Squid, Circus Wheel, Crazy Barrel, and Bottoms Up.

Located below the Sky Tower was the park’s signature Grand Carousel. For this prominent, park-front attraction, Sea World acquired a 58 year old Philadelphia Toboggan Company carousel. The ride originally operated as the Savin Rock Carousel, at the Savin Park Amusement Park midway in West Haven, Connecticut. Savin Rock closed down in 1967 but Magic Mountain was able to scoop up the classic amusement ride. But the park had their work cut out for them—the ride had severely deteriorated over time. The original organ had ceased to work and during a sloppy refurbishment in 1957, workers spray painted the ride’s horses, speckling over the original ornate jewels and gold-leaf decoration.

To return the antique attraction to its former glory, the park hired Action Animation Co., in Fullerton, California. Over 18 months and with a $100,000 budget, workers recarved and repainted the 64 hand crafted, white pine horses. At the top of the carousel, the original Rococo and Italian Renaissance-styled sculpture work was restored and the pastoral-scene panels were repainted. Finally, the attraction’s 3,800 lights and paper-roll organ were fixed and the impressive wheel shined and whined with all its original glory. As Doc Lemmon boasted to the press, “It might have been easier to build a new one from scratch, but this one is a classic.”

The “golden spike” ceremony for the Funicular.

Connecting the Grand Carrousel to the Sky Tower was the Funicular, a cable-driven transportation ride. Furnished, in part, by Intamin A.G., the ride would send two 70-passenger multi-tiered vehicles up and down the mountain. By late October, the track was installed with at least one vehicle on the line. To commemorate the ride’s installation, Magic Mountain hosted a “golden spike” ceremony with Los Angeles County Supervisor Warren Dorn. The Supervisor sledgehammered in the final pin while Doc Lemmon nervously held the spike steady and Thomas Lowe, the Newhall Land president, crouched cautiously nearby. Intamin would also produce the park’s sky-bucket ride, Eagles Flight. The final transportation ride, a mini-monorail called Metro, would be manufactured by Salt Lake City’s Universal Mobility. The simple, I-beam monorail circled the northern side the the park and featured three stations, including one tunneled through the mountain itself.

Two of the park’s signature rides would be produced by growing rides manufacturer Arrow Development—the Log Jammer log flume and The Gold Rusher mine train roller coaster. Arrow Development, a machine shop-turned-ride-manufacturer as a result of their comprehensive ride construction for Disneyland, was fast on their way to becoming an industry leader (a story worthy of its own telling, later). The firm began developing the log flume concept in 1962 and installed their first prototype, a flume named “El Aserradero”, at Six Flags Over Texas in 1963. A few months later, Arrow installed their second log flume, called “Mill Race”, at Cedar Point, in Sandusky, Ohio—during the time that Doc Lemmon was General Manager there. In 1966, Cedar Point officials would confirm that their log flume was one of the most popular attractions driving attendance.

By the time Magic Mountain ordered Log Jammer, log flumes were fast becoming tried and true theme park attractions. Log Jammer was built to take advantage of the park’s hilly terrain. The ride featured two lift hills, a winding and bumping layout, and two drops—including a final, 90 foot drop into Whitewater Lake. And yet still, owing to the custom-designed nature of the attraction, there were always new kinks and challenges to work out. In the book “Roller Coasters, Flumes, and Flying Saucers,” Arrow Development founder Karl Morgan recited a story where Magic Mountain maintenance workers failed to understand the intricacies of the new flume’s 40,000-gallons-a-minute water flow:

“I went out to lunch, and the last thing I said was, ‘Be sure to open that valve and drain that lower section before you start the ride, because if you don’t, it will dissipate all the energy.’...We came back from lunch and we didn’t know it. I saw the water all over [raised up over the trough and over the plantings] and knew what they did right away. They failed to open that valve. They didn’t think I was serious when I told them about it.”

And then, there was The Gold Rusher, a mine train roller coaster. In a story for another time, Arrow Development designed the roller coaster components of Disneyland’s Matterhorn Bobsleds, which was the world’s first steel tubular roller coaster when it opened in 1959. Arrow spent a great deal of time trying to covert the single-vehicle Matterhorn ride concept into a more traditional roller coaster design, with longer trains. Again, their first prototype, the “Runaway Mine Train” was installed at Six Flags Over Texas in 1966. Only a handful of mine train roller coasters had been installed by the time The Gold Rusher was built in 1971. The concept of a steel roller coaster was still rather new at the time.

Arrow Development would furnish two additional rides for Magic Mountain’s opening year—the Grand Prix automobile ride and El Bumpo, a bumper-boats attraction. Intamin would supply the Galaxy “double Ferris wheel”. As for the other opening day flat and round rides, I couldn’t find any further information. Wikipedia lists manufacturers for each of them, but I’m not sure where that information comes from.

Flowers, Food, and Finishing Touches

By January, many of the park’s 70 structures were fully standing or being constructed. Eugene R. Wade, the director of construction (and then the ongoing director of engineering) commanded a workforce of up to 300 construction workers and managed up to 25 construction projects at a time, with more always one week away from starting. The theme park’s architecture ranged from old-Spanish, to Victorian, to ultra modern, requiring a wide variety of skills and crafts to produce. Boasting about the sheer volume of infrastructure works required, Wade enumerated: “We moved more than 400,000 cubic yards of earth, poured more than one million cubic yards of concrete, strung more than 50 miles of electric wire, dug more than 1,000 miles of sewers, planted more than 7,000 trees, and carpeted more than two million square feet of ground with flowers, shrubs, grass, and other cover.”

On that last point, it cannot be understated how valuable and impressive the theme park’s landscaping efforts were. To transform the park’s dusty hillsides into a bonafide sapling forest, landscape architect George DeVault and the Robert E. Sapien Inc. landscape development firm commanded a landscaping budget of $1,000,000. Included in the 7,000 planted trees were mature, 60 foot tall trees rescued from the Castaic Lake reservoir basin, which was expected to begin filling imminently. To accomplish this, teams used a Vermeer tree spade, one of three operating in the state of California. As buildings were completed and equipment was withdrawn, DeVault’s team swooped in to install the 50,000 flowers, shrubs, and bushes that filled in the ground cover. Once planted, the park maintained a workforce of 26 gardening and nursery team members to maintain budding vistas.

Food and Beverage manager Max Sloan (right) reviews training procedures with Supervisor Dennis Bowman (left).

As buildings were completed, work also ramped up on kitchen equipment installation and the finalizing of menus. The park’s first director of food and beverage, Max Sloan, came to Magic Mountain from a career at Disneyland. In an early advertisement, Max waxed: “Good food in inviting surroundings is a prime element of the Magic Mountain concept...Our aim is to make dining, whether on hotdogs or steaks, as much a part of the Magic Mountain experience as the rides, dancing, shows, and entertainment.” The park was expected to feature a wide variety of food, including barbecue, fish and chips, pizza, chili, enchiladas, hot dogs, chicken, and steaks. The Painted Pullet, located between Log Jammer and Valencia Falls, would serve chicken and sides for just $2. At the top of the mountain, the Four Winds Steakhouse would serve steaks “at reasonable prices”. For Doc Lemmon, fair-priced food was considered a “public relations effort” and was intentional as a means of inspiring repeat visits from guests. Finally, in addition to the primary restaurants, there would be 23 star-shaped snack shops to provide traditional theme park fare like popcorn, ice cream, and coffee.

Shakes, Setbacks, and Staffing

Forty-one seconds after 6:00 AM, on February 9, 1971, a magnitude 6.5 earthquake emanated from San Fernando, California. The shaking lasted 12 seconds and sent damaging waves across the Southern California region, killing over 50 people, injuring hundreds more, and causing over $500,000,000 in damage. Included in the damage was the collapse of portions of the Interstate 5 and 14 freeway interchange in the Newhall Pass, much of which was still under construction. On the other side of the Newhall Pass, just 15 miles away from the earthquake’s epicenter, Magic Mountain was rocked.

Still, the emerging theme park fared remarkably well. Park officially initially estimated that the construction site suffered $50,000 in damages but that number was revised to $10,000-$15,000 after an assessment by structural engineers. Most significantly, a batch of yet to be installed electrical equipment was damaged in the shaking. Naturally, all eyes were on the 384 foot tall Sky Tower, but the structure showed no signs of damage. Construction forged on and by the beginning of March, the American flag was hoisted atop the observation deck, officially topping off the tower.

Picket lines drawn at Magic Mountain.

Though the construction timeline was hardly impacted by the disastrous San Fernando Earthquake, a labor-dispute would lead to an ill-timed work stoppage. On April 1, with two months until opening, union plumbers walked off of their jobs in protest of the apparent use of non-union plumbers. The walkout (which was never sanctioned by union leadership) inspired further work stoppages as other union construction trades refused to cross the picket lines. In total, 70% of construction work was brought to a halt. On April 8, a Federal district court judge approved a restraining order against the picketing. With a National Labor Relations Board hearing scheduled for May, construction work resumed at the Mountain. The meeting was later cancelled when union leadership proactively agreed to discontinue further picketing.

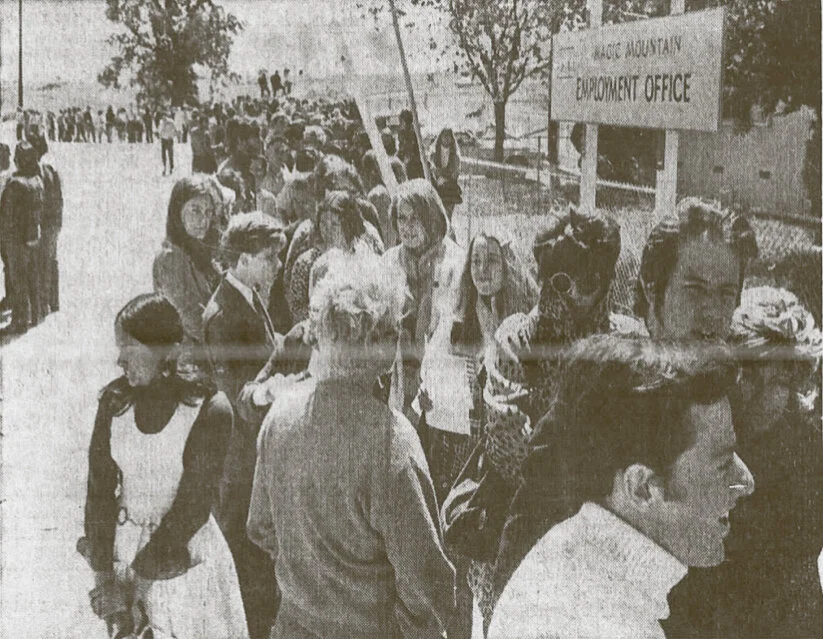

With construction labor returning to work, focus instead shifted to staffing the theme park for normal operation. On April 21, Magic Mountain began accepting applications for 1,100 jobs in a wide range of theme park operations fields—guest relations, maintenance, wardrobe, first aid, merchandising, food and beverage, sales, janitorial work, cash control, warehousing, rides and attractions, and various clerical duties. The park admitted that most positions were seasonal and would run from May 21 through September 12. Personnel Manager Ronald Niner told the press that he was looking for young people to work because “we are a youth oriented park”. “We are most interested in people who will extend that extra bit of friendliness,” he clarified. Applicants would be evaluated on availability, attitude, and appearance. Of course, men would have to cut their hair shorter to meet the park’s dress code—a big deal in 1971, a time when the term “longhaired youths” was an actual insult bandied about by fearful adults.

In addition to hair politics, 1971 was challenging year for employment in Southern California, adding intensity to the demand for Magic Mountain’s theme park jobs. The unemployment rate in Southern California reached nearly 7%, a whole point ahead of the national average. This was fueled, in part, due to cutbacks in defense contracts shuttering whole portions of the local aerospace industry. 57,000 aerospace workers were estimated to be out of work in 1971, alone, and they were included among the nearly 1,000 people who showed up early on April 21. With a long line for theme park jobs and a haphazard way of staging and processing the group, local papers depicted a mad rush for employment. The Signal surveyed the applicants, writing, “housewives with small children, couples, young men, some Chicano and black, many with long hair, students and older men, all stood in line to apply for jobs.” The two receptionists managing the queue were quickly overwhelmed and additional help swooped in to process the applicants.

A line of young adults and students queueing at the Magic Mountain Employment Office.

Despite the mad rush, when the dust settled, many positions remained unfilled. The park had expected to only hire 1 in 15 applicants but with less than a month to opening, Ronald Niner calmly shared with The Signal, “we still need about 200 more people, and perhaps more if any of the 600 committed do not show up.” While aerospace industry and “hardcore unemployed” workers were included among those who committed to roles, the majority of new hires were Los Angeles and local area students. With three weeks to go, day shifts were still available (a big deal in the theme park industry!).

A Hairy Finish

With positions open and two weeks to go, Magic Mountain began training their fresh recruits. Among the trainees, foreman were selected and ride cycling started—at least for those rides that were ready to go. So much work had been done to get to this point. And there was still so much to do. But Magic Mountain officials committed to a May 29th opening date and were unwavering from this decree, not wanting to miss out on Memorial Day weekend. For all of their attempts at controlling the narrative, no one was really sure how opening day would turn out.

In the Valencia Valley, residents started getting excited for their community preview night, organized by the Newhall-Saugus Jaycees on May 27. Meanwhile, theme park hires everywhere began making preparations for their new roles. For some (and later for many), Magic Mountain was their first job and they had to fit the part. Many young men were faced with the need to cut their hair. According to one anecdote in The Signal, such a scenario unfolded in a Newhall barber shop:

“How do you want it?”, asked the Barber.

“Got to have it short and neat”, replied the young man. “I’m going to work at Magic Mountain and I won’t get the job if I look this way. Can you cut around the sides, leaving the top?”

“I know, I know. I’ve given three of these this week already,” chuckled the Barber—“One Magic Mountain cut coming up!”

The stage is set and the park is ““ready”” to open! Check back very soon for Chapter 3 on the theme park’s opening season!

Photo Credits

Cover Image - Panorama, Hilltop view of Magic Mountain Construction - Amusement Business. March 13, 1971. From Vintage Disneyland Tickets.

High Riser, Construction Photo of Sky Tower with Park - Amusement Business. March 13, 1971. From Vintage Disneyland Tickets.

Hexagonal Tower Concept Art - Intamin Tower Brochure. Shane’s Amusement Attic thread on Theme Park Review.

Funicular Golden Spike Ceremony - From “Spiked with Gold” Valencia advertisement. The Signal, 11/27/1970.

Food Training Review - The Signal, 3/15/1971.

Plumber Pickets Magic Mountain - From “Plumbers Set Up Picket Lines”. The Signal, 4/2/1971.

Applicants - The Los Angeles Times, 4/22/1971.