Magic Mountain

Chapter 1 - A Mountain Born from the Sea

Estimated Read Time: 18 min

On an oven-hot Thursday, in August of 1969, members and guests of the Newhall-Saugus-Valencia Chamber of Commerce crammed into a local clubhouse for a lunch time presentation on the new amusement park coming to their community. Nearly one year prior, the organization caught wind that Sea World, the aquatic-animal park located 150 miles south in San Diego, was looking to build a “rides park” in the Valencia Valley. After ten months with only an handful of articles, rumors, and press releases, the 120 guests were hungry for information about the fabled project. The crowd shuffled to their tables and were served an economical, filling suburban feast of cured-ham, canned peas, french fries, side salads, and bottomless coffee. As the group began polishing off dessert (globs of green and red jello, topped with whipped cream), their presenter made his way to the front of the room.

Eugene “Doc” Lemmon points to a scale model of Magic Mountain, surrounded by Newhall Land & Farm Company President Thomas Lowe (left) and Sea World Founder and CEO George Millay (right).

The speaker was Eugene R. Lemmon (pronounced “La Mon”—but he went by Doc). Lemmon was Sea World’s executive on the Valencia Rides Park project. He was a middle-aged man with a round torso and puffy, square face. He stood before the crowd in a charcoal-grey suit, dark striped tie and monogramed handkerchief. He was calm and prepared, and waited patiently for his audience to finish their desserts. This wasn’t his first pitch (and it would hardly be his last); selling an amusement park was a marathon—and he had been running for some time.

Lemmon’s work with theme parks began in 1953, when he was in business with his buddies at the consultation firm Stanford Research Industries. Walt Disney hired SRI to help find the best location for his new “Disneyland” idea. The research group identified Anaheim, a quiet farm town 30 miles south of Los Angeles, as the best location for cheap land, access to roads, and proximity to a population center.

Walt would go on to hire many of the SRI guys to serve in key Disneyland positions and Doc was hired as the park’s new Director of Operations, shaping many of the magic kingdom’s early operational practices. Doc served in this role until 1961, when he accepted an offer to become the General Manager of Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio. Lemmon met his wife in Sandusky and worked at Cedar Point until 1964, when he left to consult on operations for the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. From there, he returned to California to spearhead the Cal Expo, before being poached by Sea World Inc.

Lemmon was one of the most experienced theme park operators of his time. But today, his job was to convince local suburbanites that his park would be good for their community. As the party guests set down their dessert spoons, Doc cleared his throat and introduced himself. In a warm, Texas-drawl, he began with a few friendly jokes to win over the crowd. Then, it was time to get into what everyone was there for. Motioning to a collage of artwork staged along the side of the room, he began:

“That—is much of what our park is going to look like”.

As the audience turned their attention to the colorful concept renderings of an idilic, hilltop amusement park, Lemmon began to describe the park in his mind. There would be a log flume here. And a double Ferris wheel here. And on this side, a “runaway mine train” that didn’t rattle like those old wooden coasters of yesterday. And over here, a nice “children’s garden”, for the young kids. And the best part: “You can ride all the attractions you want merely for the admission price”—a novelty, as Californians were accustomed to the Disneyland-system of purchasing tickets to access the attractions.

The park was to occupy 80 acres at the hilly center of the property and feature a sky ride, funicular, and mini-monorail to help scale the inclines. Built into the center hill would be a 7,000-seat auditorium for rotating celebrity entertainment (included in the cost of a ticket, of course). And at the very top of the mountain, a regal observation tower would be perched 300 feet above the park, like Seattle’s Space Needle. Estimating the park would cost $15 million dollars and feature “something for everybody”, Lemmon did his best to woo the intrigued locals.

As the presentation wound down, Lemmon outlined the next few months, declaring, “We’ll be doing preliminary site preparation there until the first of the year, and then we’ll break ground. After that—boom, we’re on our way.”

“We really don’t have a name for it yet. I like to call it ‘Magic Mountain’. I put that on all the drawings I show my board—maybe they’ll learn to like it.”

The Expanding Sea World

In 1955, when Disneyland opened its gates to the world, eager businessmen immediately began to dissect and analyze the alchemy that made the park such break-out success. America was young, growing, and hungry for a slice of the Disneyland-experience and companies went to work to fill the void.

Lesson one: There was no longer a need to cram amusement parks into small city plots or on beach boardwalks. Parks were traditionally shackled to these spaces, dependent on city center populations and public transportation networks. But Disneyland showed that you could build your park in the ‘burbs and the boonies, where real estate was far cheaper. As long as a city was nearby and road existed for folks to get to you, your park was good to go. And thus, the regional theme park was born.

The 1960s was a decade in which theme and amusement park development began to ramp up. New players arrived on the scene and many existing attractions started moving closer to a Disneyland-like experience. In 1961, Six Flags Over Texas opened in Arlington and Huston’s Six Flags AstroWorld would follow in 1968. Anheuser-Busch, reaching back to an old company concept, opened a Busch Gardens animal park in Tampa, Florida in 1959. A second Busch Gardens would open in 1966 in Van Nuys, California, and by then, both parks featured a monorail attraction. In 1964, the modern Universal Studios backlot tour began and soon after, attractions were being added to keep the tour fresh and exciting. And then there was Sea World.

Founded by George Millay and several of his UCLA buddies, Sea World opened on March 21, 1964 in San Diego, California. The original Mission Bay park was located on just 22 acres and featured 92 species of aquatic animals. The animal exhibits and shows were staged among landscaped avenues and the space was united with a Polynesian theme. Though out of fashion today, the original Sea World earned a positive reputation as a circus for sea animals. Included among the shows and aquariums was a Japanese Village pavilion and hydrofoil boat rides, but no “Disneyland”-style attractions.

A post card of the original Sea World, prior to the park’s rapid expansion. The park entrance is the pointed building to the right. The Japanese Village can be seen at the top right and the central, curved-roof building is the Theatre of the Sea.

The park was a break-out success, particularly with international tourists. Expansion plans were drafted immediately. In 1967, the park opened Atlantis, a Mediterranean-themed restaurant, and built a gondola sky ride to ferry park guests 1,410 feet across Mission Bay to the venue’s swanky, aquarium-walled cocktail lounge. By 1968, Sea World was in the midst of a $2.5 million expansion program that included a new freshwater exhibit (containing an 800 seat auditorium for a fountain-and-light show), a 500 seat lagoon stadium, a new 72,000 square foot administration building, 3 new banquet rooms for Atlantis, additional landscaping, buildings, expanded parking for 800 cars, and enough land to double the park’s footprint. But George Millay’s appetite for expansion wasn’t limited to Mission Bay.

Staking a claim in the race to install parks in new regional areas, in 1968, Sea World Inc. set out to create two brand new park experiences. The first was “Sea World East”, a second Sea World aquatic animal park catering to the eastern United States. In November of 1968, the company announced that a Sea World park would be constructed at Geauga Lake in Ohio, 25 miles southeast of downtown Cleveland. Sea World Ohio would be designed much in the same fashion as the original park and feature animals trained in San Diego. The plan was to fly the animals to Ohio every spring and return them to San Diego before the harsh Midwest winter settled in.

If the prospect of flying whales across the country seems tricky (at best), it may be easy to understand why Sea World was also interested in experimenting with a “rides park”. Amusement park rides required a heavy initial investment, but did not require the ongoing training and veterinarian resources that Sea World was growing increasingly familiar with. Thus, in 1968, Sea World hired Doc Lemmon with the intention of constructing a rides “theme park” in the style of Six Flags Over Texas. Doc went to work immediately.

But Why Awesometown (Valencia)?

For this first “rides park” experiment, Sea World looked for property in southern California—something near to the original park, but not too near. The directive was to find cheap land within a close proximity of a freeway. Sticking to the aquatic theme of the original park, there was a desire to build on the water. But where could you find water-front property for cheap? Perhaps, in a Lex Luther-like calculation, where water did not exist, but where it could be.

Castaic Dam under construction in 1971. The dirt area south of the dam (lower-right) would feature a lagoon, likely near the desired first site for Sea World’s new park. [Click to Expand]

In 1968, construction was underway on a California State Water Project dam northwest of the Valencia Valley, right off the Interstate 5 freeway. The resultant body of water would be called Castaic Lake and the man-made reservoir was expected to open for recreation in 1972. Despite sitting just one mile away from a prison complex, the site ticked all of Sea World’s boxes. Millay eyed 200 acres of Los Angeles County-owned land, immediately south of where the reservoir was being constructed. And so in September of 1968, Sea World initiated a series of meetings to pitch the project to County Supervisor Warren Dorn and obtain a hand-shake agreement in support of the project.

But the secret meetings were leaked to the press. As reporters pressed Dorn and Millay for details, the men backpedaled from their intentions. Only Los Angeles County Recreation Chief Norman Johnson shared any details of the idea in incubation—

“It’s a grandiose concept. If you can sort of imagine combining an aviary like Busch Gardens, add Marineland or Sea World for their shows and exhibitions, throw in the commercial rides of Disneyland, and you have the idea…It’s sort of like a giant amusement park in an aquatic-park-like atmosphere. The difference from Disneyland is that there would be one admission price for getting in that would include the rides.”

With Sea World’s cover blown and the risk of a political fight, George Millay lost his appetite for the Castaic parcel. Now speaking to the press, Millay admitted that Sea World was interested in building a new park. He revealed that eight or nine sites “anywhere from west San Fernando Valley to Ventura” were being considered for the new park. It’s unclear if Millay’s statements were meant as a red herring or if Sea World was truly considering sites in Chatsworth or Ventura. But in the final months of 1968, rumors began to emerge that Sea World was in talks with the Newhall Land and Farm Company for real estate in the Valencia Valley, near the original Castaic Lake site.

An aerial photo of the Magic Mountain site from 1968. For reference, the blue marking is the location of Valencia Falls, the park’s entry plaza landmark. The yellow dot is where the Sky Tower now stands. The parking lot would go in the flat grazing area (north) and the “back side” of the park is where the livestock pens are. Notice that the Interstate 5 freeway is under construction at the bottom of this photo. [Click to Expand]

Sea World’s rumored partner, the Newhall Land and Farm Company, was the primary real estate development company in the Valencia Valley. Incorporated in 1883 by the five sons of Henry Mayo Newhall, a California gold rush-era auctioneer and landowner, the company managed 143,000 acres of land north of Los Angeles. While the company initially focused on resource extraction (farming, mining, or oil drilling), Los Angeles’s growing urban sprawl began to change the math. In 1953, the company commissioned a report to investigate the development farmland for residential use (incidentally, this research was provided by Stanford Research Industries, the same year they were consulting on Disneyland). By 1965, the Valencia Master Plan was approved by the Los Angeles County Planning Commission and construction on the cookie-cutter community of Valencia was started.

Transforming the dusty chaparral of the Valencia Valley into a desirable place to live required more than single family homes. The Valencia Master Plan made accommodations for industrial development “minutes from everyone’s driveway” and a city center featuring civic services, healthcare facilities, and more. Additionally, schools were integral to this plan, as was the area’s first college, the California Institute of Arts. Recreation was also considered. Newhall Land enticed prospective residents by advertising a new golf course, local streams and nearby lakes (including the future Castaic Lake), and picnicking opportunities.

For the Newhall Land and Farm Company, Sea World’s amusement park was a serendipitous, last-minute jewel in their master-planned crown. The park would attracted tourists and travel-dollars from the Los Angeles area, supply jobs, and draw attention to their new community’s amenities. And there was a calculation that the park could increase the value of their investment. In a May, 1970 advertisement for living in Valencia, published in The Los Angeles Times, Newhall Land openly boasted about their expectations of the park’s impact:

“Remember what Disneyland did for property values in and around Anaheim? Sent ‘em way up. You should be living here when the Mountain comes to Valencia in the spring of 1971. The value of your home should be all uphill from there.”

With so much at stake, not only did Newhall Land lease the park’s real estate—a hilly ranching area at the corner of US Route 99 (The Old Road) and the Santa Clara River—but the company became a fully-fledged partner on the project. Budget-stretched, expansion-hungry Sea World welcomed their participation.

Presenting: The Valencia Rides Park

On January 15, 1969, a deal was announced: Sea World Inc. and the Newhall Land and Farm Company declared a joint-venture to develop a new amusement park on the hillsides across from the Valencia Golf Course. The park would feature 16 themed rides planned on and around the large hill at the center of the property. Project architect Randall Duell boasted, “we are going to build our big show on a mountain”, further explaining, “actually, there’s a series of four hills fused into one ridge.” David DeMott, Executive Vice President of Sea World, declared “it will be a themed park”, but shared that a park theme and name had not yet been chosen. He pointed to Six Flags Over Texas as a comparable to the type of experience he envisioned. Calibrating Southern Californian expectations, DeMott went on to share “while it will definitely not be a carnival, it will not be as sophisticated as Disneyland.” Construction on the new park was expected to begin in February of 1970, with an anticipated grand opening in the spring of 1971.

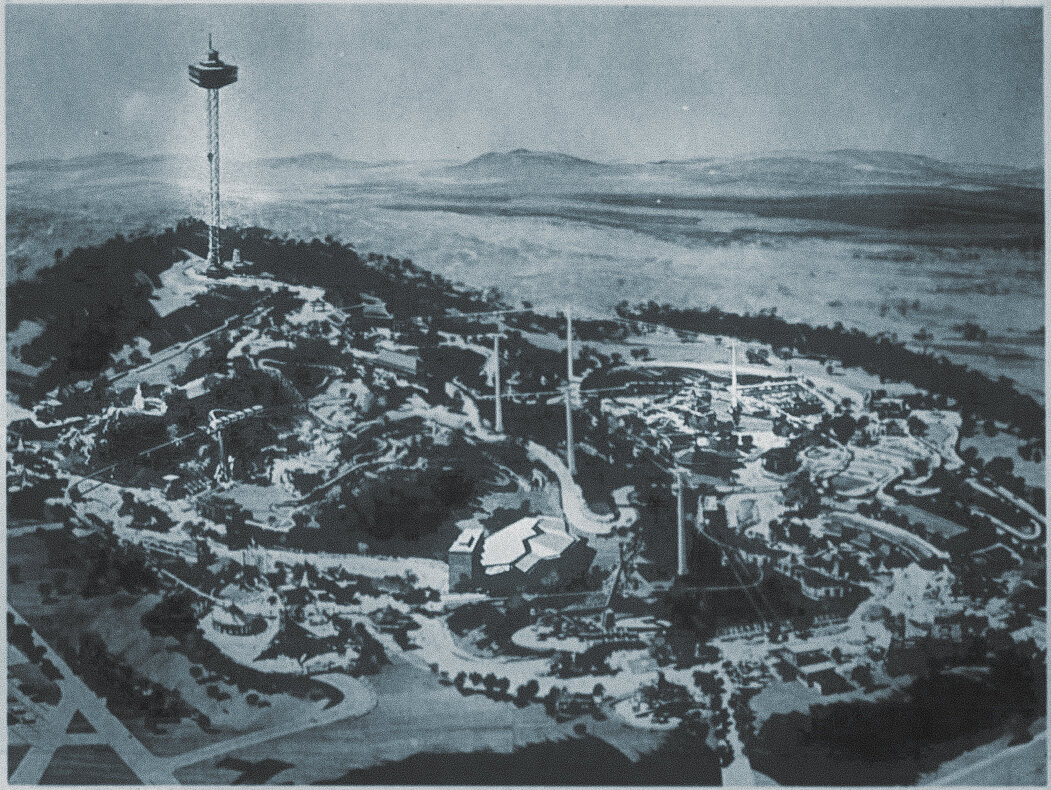

Beyond these details, little was announced or revealed about the new project until May of 1969, when concept art was released to the press. The artwork, furnished by Randall Duell’s architectural firm, was remarkably spot-on to what would open two years later.

A newspaper clipping of Randall Duell & Associates’ concept art of Magic Mountain.

The rendering showed parking lot trams ferry arrivals from a massive parking lot on the lower, northern edge of the property. From there, guests would pass through an arrival plaza prominently featuring a cascading waterfall. To the left, the pathway ended with a carousel and funicular up the hill. To the right, guests would pass a log flume, mini-monorail, a massive amphitheater, and a children’s ride area. From there, a ‘double wheel’ two-armed ferris wheel, which cycled guests on one side as the other side was loading and unloading. The park’s pathway then curved around the northern edge of the hilltop, past a few spinning flat rides and a games area. There were bumper boats, bumper cars, and cars not for bumping. Guests could take the monorail, a gondola ride, or a series of winding pathways around the roller coaster to the top of the mountain, where the park’s signature observation tower stood tall.

The concept art depicted a kinetic theme park experience, full spinning, splashing, twirling, and transportation rides. The landscaping was lush and waterfalls, ponds, and lakes flooded pockets on each side of the hilltops. The park catered to young kids and families, but boasted three dance areas and celebrity acts to draw in the teenage-dollars. There truly was something for everybody.

But the artwork wasn’t enough to convince some local residents. The local chamber of commerce began to grumble that park officials made no effort to seek their feedback, integrate with local leadership, or simply share plans and updates on the new project. Some feared that if finances fell through, a half-finished park would blight the community. And other residents began to fear that a youth-oriented theme park may attract “undesirable elements” to their valley. The Signal, the local newspaper, ran a piece on how Anaheim-area crime increased in the wake of Disneyland’s opening and local Sheriffs Deputy Lt. John Knox confessed that the park hadn’t yet consulted with the local emergency services—“The only plans we’ve read is what we’ve heard in The Signal.”

As park planners prepared to meet before the Regional Planning Commission to file for land zoning changes, a growing awareness emerged that local opposition could stifle their aggressive construction schedule. And sure enough, at a July 15th zoning change hearing, concerns were voiced. Doc Lemmon, representing the park, argued that “sound business practices, good engineering, sound management, and built-in safeguards would prevent an economic or geologic catastrophe.” He went on to explain that his experience at Disneyland taught him how to address rowdy teens and that “the development would be geared to families rather than teen-agers.”

When the Planning Commissioner announced his agency would deliberate for 45 days before rendering a decision on the zoning change, a compromise was struck—the Sea World team agreed to meet with homeowner groups and the local Chamber of Commerce to share their plans with the community. This approach seemed to satisfy everybody. On August 19, at the next zoning change hearing, local Thomas Neuner withdrew earlier concerns, stating “all of my objections had been answered.” The Regional Planning Commission voted to approve the theme park’s zoning changes.

Selling an Amusement Park (Is a Marathon)

On June 23, 1970, 21 months after news leaked that Sea World was planning a rides park in Valencia, a lavish preview event was staged for the park-to-be. 400 invitees, consisting of members of the press, Valencia Valley community leaders, Los Angeles County employees, and Newhall Land and Farm Company representatives, squeezed in to the grand ballroom of the Sheraton Universal Hotel, in Universal City. The bars opened early. Eventually, guests listened to remarks from Tom Lowe, the President of the Newhall and Farm Company, George Millay, and Doc Lemmon while a “short-skirted, pretty” secretary modeled a carousel horse.

After these remarks and an 8-minute promotional video, various government representatives were brought to the stage for more speeches. As local, state, and federal government speakers waxed on about how meaningful Magic Mountain would be—for their particular brand, philosophy, or district—the crowd began to grow listless. As the last speech finished, Doc Lemmon returned to the podium to confront the disinterested crowd. He was scheduled to be the final speaker and was meant to facilitate a question-and-answer session but sensed the crowd was checking out. For a man who had made a career of operating amusements and entertaining people, this was an easy problem to solve.

“Would you rather ask the questions from your seats or from the bar?”

Immediately, the crowd shuffled to the bars.

Well, that should do it for my first pass at a Magic Mountain history. Join me soon (I hope!) for Chapter 2, which will cover the new theme park’s construction!

Photo Credits

Cover Image - Artistic Rendering of Magic Mountain - From Valencia advertisement “MAGIC MOUNTAIN is the newest focal point for Valencia recreation”. From The Signal, 5/14/1971.

Doc Lemmon Pointing to Scale Model - From “Magic Mountain’s Big Press Party”. The Signal, 6/26/1970.

Sea World Post Card - “Sea World Mission Bay”. 1965-1969. Road-Runner Card Co. Baja California and the West Postcard Collection. MSS 235. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego.

Castaic Lake Construction - “Aerial View of Castaic Lake”. 1/19/1971. County of Los Angeles Department of Public Works. County of Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreation Historic Photo Collection.

Magic Mountain Site Aerial Photo - Flight HA_UW, Frame 24, 10/24/1963. Courtesy of UCSB Library Geospatial Collection.

Magic Mountain Concept Art - “Rides Park Valencia For Sea World”. Randall Duell & Associates. From “Sea World’s New Amusement Park”. The Signal, 5/14/1969.