The Dragon’s Gorge

Part 3 - The Death of Two Dragons

Estimated Read Time: 9 min

This is Part 3 in a 3 part series on La Marcus A. Thompson’s Dragon Gorge. If you haven’t already read Part 1 or Part 2, you are welcomed and encouraged to do so. Enjoy!

Revere Beach is a crescent shaped, three mile long stretch of coast located 5 miles northeast of downtown Boston. In 1876, the Boston, Revere Beach & Lynn Railroad began operating and brought hundreds of thousands of visitors to the area. Capitalizing on this popularity, in 1895 the newly-created Metropolitan Parks Commission acquired the beach and cleared the old structures that dotted the shore. Revere Beach would reopen in 1896, proudly boasting the title of being the first public beach in the United States.

Chasing after throngs of beachgoers, it wasn’t long until amusements began to show up. The first amusement park was Wonderland, followed by a Luna Park (a very popular name for early amusement parks). Soon after, games, theaters, and rides were found all along the Revere Beach coastline—including another Thompson Scenic Railway Company Dragon Gorge.

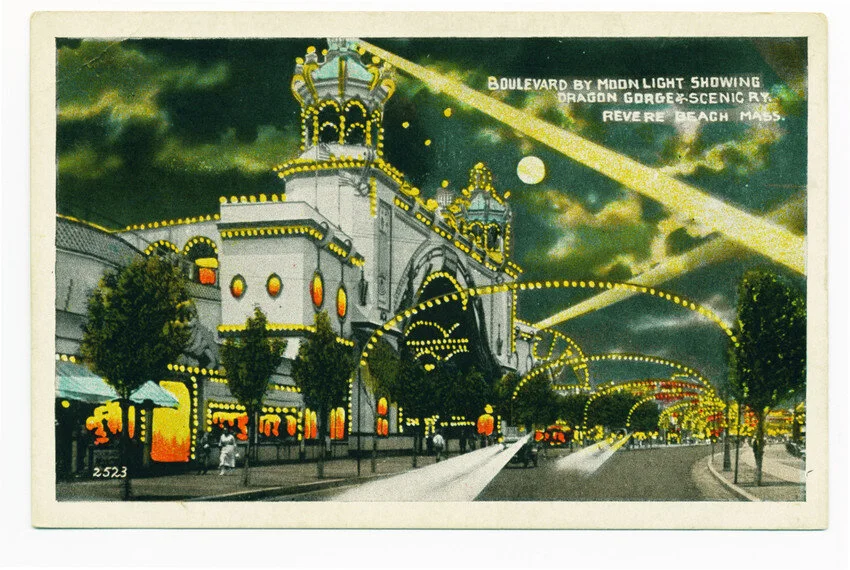

Of the three incarnations of the Dragon Gorge, the Revere Beach version is the least well documented. Short of what physically lurks in Boston-area libraries and archives, there doesn’t appear to be any good description of the ride experience available online (COVID-19 has limited my research to the web). Postcards of the structure give a little bit of insight: The Revere Dragon Gorge building was white and green, dotted with popcorn light-bulbs, and featured two American flags atop the familiar, pagoda-themed towers. Inside the arch cutout was a beautiful diorama, with ride tracks among rock work in the foreground and an idlic ocean vista painted in the background. Small trees lined the boulevard in front of the structure. And standing at the bottom corners of the arch, our now familiar friends—two beastly dragons, looking menacingly at each other.

The Revere Beach Dragon Gorge was smaller than the Ocean Park model and the ride appeared to be fully enclosed in within the show building. Similarly, space in the Dragon Gorge building was sub-let out to other businesses—primarily, it would seem, amusement gaming companies. Over the building’s life, the attraction housed a shooting gallery, cigarette shooting game, and a “Japanese Rolling Ball” game operated by Joe Imoni, a Japanese immigrant.

What was well reported on, was the Thompson Scenic Railway Company’s continuing frustration with the local government in Revere. Revere Beach seemed to be a highly regulated, high tax environment. The local government dictated which amusements could operate for the season and charged high license fees. At one point, a separate license was required to operate on Sundays. As early as 1913, the company joined with other amusement concessioners in a formal protest over the high cost of “superfluous police protection”, alleging that far more costly police officers were present at Revere Beach than was needed. The group also protested a statute that their businesses could not operate past 11:00 pm. Then in 1915 (in what could be perceived as consumer protection or police harassment), the Metropolitan Park Police raided and closed several of Revere Beach’s “games of chance”, including Joe Imoni’s rolling ball game in the Dragon Gorge.

The Thompson Scenic Railway Company’s frustration boil over in 1922 when company manager Frank Darling went before the local committee to protest the latest tax increase. Darling complained,

“Revere is the highest taxed of 21 places in which our company operates. In no other place is the license fee more than $25 and in no other place have we to pay for police protection ourselves.”

Darling went as far as to list out the company’s Revere Beach finances, stating that their two scenic railways generated $95,000 in revenue but cost $84,000 in expenses, taxes, and fees. When considering “depreciation or insurance which we [the Thompson Scenic Railway Company] have to carry ourselves”, Darling suggested that business was not sustainable. In a final warning, he shared that the Thompson Scenic Railway Company would have to “have to withdraw from the beach unless conditions are changed in the immediate future.”

Despite the scathing rebuke, it would seem that no changes were made. On April 7, 1923, the Thompson Scenic Railway Company listed the Dragon Gorge property for sale in the local paper, The Revere Journal. Unfortunately, the body of this advertisement is unreadable (via digital scan), but inside the paper, an opinion piece lamented the loss of this amusement icon. The Journal wrote: “It will be most unfortunate to have these people abandon any of their Revere amusement places because we greatly need this high type of business man and should give them all possible encouragement.” The sale, it seems, went through.

The Revere Beach Dragon Gorge may have operated for a few more years under new owner. But, according to one report in 1927, after 16 years of service, the Dragon Gorge was demolished to make way for a new roller coaster. Only one "Dragon Gorge” was still standing.

Over the first four decades of the 20th century, America changed quite a bit—and for a while, The Dragon’s Gorge at Coney Island kept up. In 1917, it was reported that the ride had lasted over a decade because “its beautiful scenes changed each season”. After all, turn of the century news stories must have soon felt outdated. In their place, new (less time-specific) scenes were installed. Papers reported that passengers now zipped through island tropics, Africa, the River Styx, and even Hades, playing on riders’ sense of mystery and exoticism.

But by the 1940s, The Dragon’s Gorge was more an odd novelty than a star attraction. One article referred to the ride as an “old standby”. Another lumped it in with “milder” rides, a stark demotion from the thrilling throne it once occupied. The ride lost its luster and years passed without mention. The Dragon’s Gorge survived a fire, accidents, government investigation, the Great Depression, and was squeaking through its second World War.

Then on August 12, 1944, Luna Park employees heard sputtering coming from a wash room under the Gorge. They went in to investigate and saw sparks raining from an electrical fixture in the ceiling. A fire broke out. The employees used hand extinguishers and tossed water, but the flames continued to feed on the structure. The ride was operating and a car with seven or eight passengers had just been dispatched. As smoke once again began to fill the ride’s tunnels, operators quickly stopped the ride and evacuated patrons from the structure. Out front, smoke allegedly began to emanate and billow from the Dragons’ mouths. Nervous barkers encouraged Guests to “come back later” but continued with their spiels. For fifteen minutes, Luna Park was business as usual. Then the alarms sounded.

An aerial photo of the fire fight. The Dragon’s Gorge is near the center of the photo and in the upper left is the park’s electric tower.

It was a hot summer day and Luna Park’s wooden structures were as vulnerable as ever. An ocean breeze began to whip up the flames and embers were sent flying hundreds of feet around Coney Island, igniting many more fires. Rides and buildings were evacuated and circus animals were secured and moved away from the flames; spectators crushed inwards to watch the blaze. 42 engine companies, 16 truck companies, and a rescue squad descended upon Luna Park as flames began to soar 400 feet in the sky. The smoke could be seen for miles around New York City.

Two hours later, the blaze was subdued. So was Luna Park. Lost was the Boomerang. And the Dodgem. And Shoot the Chutes, Aqua Gal, Spook Street, Hollo-Plane, Mirror Maze, Harem Scarem, and the shooting gallery. In fact, 20 rides and games across nearly half the park’s 16 acres had been burnt to a crisp, including two restaurants and Luna Park’s 125ft electric tower—the park’s 40 year old, iconic centerpiece.

And The Dragon’s Gorge, where the blaze had originated, was gone. At nearly 40 years old, the ride had lasted longer than most.

Discovering an image of the Ocean Park Dragon Gorge was one of my inspirations for starting The Amusement Archives. The ride is a great example of early themed entertainment and is a superb gateway into this era of amusement history. With mismatched show-scenes and plastered-canvas rock work, the ride was hardly refined. But still, The Dragon’s Gorge (and scenic railways like it) created a new baseline for what was possible with roller coasters.

The story of the Dragon Gorge also explores the early fears and failures of amusement ride safety. In many ways, these rides featured the most cutting edge safety innovations, like block signals and anti-rollback ratchets. And yet, wood construction, lax building codes, poor maintenance, and human error played some role in the demise of these attractions. Accidents and fires forced the Thompson Scenic Railway Company to carry their own insurance and fueled innovation in safety systems. But improvements made new construction cost prohibitive. These large wooden, canvas, and plaster structures, piping enough electricity to power thousands of lightbulbs, were both ahead of their time and a firefighting nightmare. It’s perhaps easy to see why in the 1920s (dubbed the “Golden Age of Roller Coasters”), designers pivoted away from theming in favor of thrilling layouts and simple design principles. That’s not to say these new roller coasters were safer or less fire prone—just that the expense and risk of theming was avoided.

The Dragon’s Gorge, it seems, was once as famous as any other well-known ride. I feel privileged to start our stories here.

As one final note, one of my favorite parks has built several architectural nods to this old icon. Walt Disney Imagineering has stated that Disney California Adventure’s The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure’s show building facade is inspired by the Dragon Gorge’s famous arch. On the other side of Pixar Pier, the Pixar Promenade stage directly adapts the Dragon Gorge’s form. Within the building’s arch is a classic Californian bandstand and atop the flanking towers, Victorian gazebos have replaced the more problematic pagodas. But the idea is there!

Cover Photo: Historic New England, Gift of Cristina Prochilo, 2018